- Home

- Roberto Arlt

The Mad Toy

The Mad Toy Read online

The Mad Toy

Roberto Arlt

Translated by James Womack

Contents

Title Page

Foreword by Colm Tóibín

Introduction by James Womack

Chapter 1 The Thieves

Chapter 2 Works and Days

Chapter 3 The Mad Toy

Chapter 4 Judas Iscariot

Biographical note

Notes

About the Publisher

Selected Titles from Hesperus Press

Copyright

Foreword

There is a particular edge to the novels and stories written in countries which lacked a stable middle class or a clear sense of social continuity. It is as though the spirit of uncertainty in these countries made its way into the very structure of the fiction which writers produced. This fiction is filled with strange choices and odd chances; the way of handling incident is rich with risk and mystery. In his book on Nathaniel Hawthorne, written in 1879, Henry James attempted to identify what novelists in New England did not have at their disposal, thus making their fiction different from that being created in Europe. His famous list was as follows: ‘No sovereign, no court, no personal loyalty, no aristocracy, no church, no clergy, no army, no diplomatic service, no country gentleman, no palaces, no castles, nor manor, nor old country houses, nor parsonages, nor thatched cottages, nor ivied ruins; no cathedrals, nor abbeys, nor little Norman churches; no great Universities nor public schools – no Oxford, nor Eton, nor Harrow; no literature, no novels, no museums, no pictures, no political society, no sporting class – no Epsom nor Ascot.’

It is easy to imagine the Argentine novelist Robert Arlt (1900 –1942) looking at this list and smiling in full recognition. The Argentine writer had the city of Buenos Aires and the army, perhaps, but beyond that only a sense of isolation. The Argentine writer had the port and the pampas, but beyond them merely a heightened sense of desolation. Like Henry James, Arlt would have understood, however, that not having a thousand years of slow progress at your disposal, as the English and French novelist did, might be gift as much as an impediment. ‘The American knows,’ Henry James wrote, having given his list, ‘that a good deal remains.’ Seven years earlier in a letter to an American friend, James had suggested that the richness of Europe was something perhaps the American novelist did not even need: ‘It’s a complex fate being an American, and one of the responsibilities it entails is fighting against a superstitious valuation of Europe.’

In New England such a struggle against ‘the superstitious valuation of Europe’ gave us nineteenth-century novels with stark imagery and memorable drama such as Hawthorne’s The Scarlet Letter or Melville’s Moby Dick, which attempted to create a world more vivid and filled with plenitude than the world outside its pages. In countries such as Ireland, Brazil and Argentina, places where poverty, social disruption and fragile institutions reigned, where form and continuity were sorely missing, the novel also took on a new and strange shape.

In an essay written in 1932 called ‘The Argentine Writer and Tradition’, Jorge Luis Borges suggested that this lack of social continuity and this sense of being on the periphery of literary culture could be seen as a gift, or a new way of nourishing that very culture. The South American writer, he wrote, by virtue of being close and distant to the centre of Western culture had more ‘rights’ to Western culture than anyone in any Western nation. He compared this enriching sense of proximity and distance with the position of Jewish and Irish writers. ‘It was enough,’ he wrote, ‘the fact of feeling Irish, different, to become innovators within English culture. I believe that Argentine writers, and South American writers in general, are in an analogous situation; we can handle all the European themes, handle them without superstition, but with an irreverence which can have, and does have, fortunate consequences.’

The years when Roberto Arlt was beginning to write were years of stress and change in Argentine society. A massive wave of Italian immigration had radically transformed the city of Buenos Aires and created a distance between the city and the pampa. Increased wealth also meant that books and ideas from outside began to matter to young Argentine writers, as the novels of Dostoevsky would matter to Roberto Arlt. Even as early as 1872 when Jose Fernandez published his great poem ‘Martin Fierro’, the theme of the solitary outsider became central to the Argentine imagination. The intensity of the immigration created a sense of rootlessness and dislocation, the sheer size of pampa and the teeming chaos of the city made their way into images of personal anguish and hostility to the social world. Images of the sad figure alone in Buenos Aires, a half-made man in a half-made place, with no society to distract him, and no possibility of any drama other than the dark, jagged drama that occurs within the alienated self, became central in Argentine literature.

In the fiction of Borges and Bioy Casares, in the novels of Arlt, in the later work of writers such as Ernesto Sabato and Julio Cortazar, the idea of playfulness was also central. These writers believed, as did Machado de Assis in Brazil and James Joyce in Ireland, that the real world could not be reflected in the pages of a book, but rather it could be re-made there, or made more strangely real there. The world could thus reflect the book. Their novels experimented with form and structure, played with ideas of character and tone. They did not dramatize moral questions, or deal with society and the individual. They did not allow domestic harmony to occur at any point in the stories they told. Their stories were fractured and irrational; their characters were happier on the street than at home, and happier, or more exquisitely unhappy, alone, than with families or associates; their narratives were more content if nothing in them could be easily tied into neat plots.

This did not mean that Borges (1899–1986), Bioy Casares (1914–1999) and Arlt operated as a group. In ‘Borges’, the massive volume, published after the death of Bioy Casares, in which Bioy wrote down all the conversations he had with Borges about writers and writing, there are many disparaging references to Arlt, as there are indeed to Ernesto Sabato (1911–2011). The fact that Arlt had very little formal education and that both of his parents were poor immigrants would not have been lost on Borges and Bioy, whose roots were deep in both cosmopolitan literary culture and nineteenth-century Argentina. Also, the literary world of Buenos Aires in the years when Arlt wrote, and in the years after his early death, was one of factions where the divisions could be based on political allegiance as much as social class. None of Arlt’s work, for example, appeared in the great Argentine literary magazine Sur – to which Borges and Bioy had close connections – which began publication in 1931.

Arlt’s novels were published between 1926 and 1932. Although he continued to write short stories and pieces for the newspapers, between then and his death he mainly worked as a journalist and a playwright. Because he was sent out to work when he was young, he developed an intimate outsider’s knowledge of the centre of Buenos Aires, streets such as Florida and Lavalle, which were elegant in these years when Buenos Aires was one of the richest cities in the world. He invokes Lavalle in The Mad Toy: ‘It was seven o’clock in the evening and Lavalle Street was showing off its most Babylonian splendour. Through the plate-glass windows you could see that cafés were crammed with customers; carefree dandies gathered in the entrances of the theatres and cinemas; and the windows of the clothes shops – which displayed legs in sheer stockings hanging from nickel-plate bars – and those of jewellery stores and orthopaedic stores all showed by their opulence the cunning of the businessmen who used their spiffy goods to flatter the voluptuousness of the wealthy.’

Arlt also knew the more miserable suburbs where the newer immigrants lived. His relationship with his father was always difficult, his childhood was seriously unhappy. When he was fifteen,

he found work in a bookshop in Calle Lavalle; soon he met a number of Argentine writers. The following year he published his first story. When he was seventeen he left home for good and began to look after himself.

Although writers and intellectuals in Buenos Aires in the 1920s felt distant from both Europe and from South America itself, Buenos Aires was a cosmopolitan place where small magazines and new ideas flourished and where there was much debate about what sort of literature this new and hybrid country should produce. Although Arlt was never close to Borges, he did know another writer who came from a cultured family, the novelist Ricardo Guiraldes; he was published in Guiraldes’s magazine Proa, as was Borges. Guiraldes (1886–1927) had travelled widely, especially in France, and was opposed to the use of stilted, literary language in novels and stories.

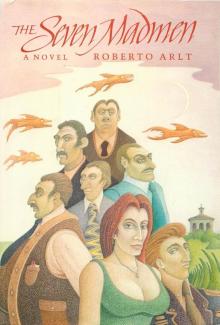

This suited Arlt. He loved the streets of the city and its slang and had much to say about them in his novels and in the column he began writing for the newspaper El Mundo in 1928. In the 1930s he travelled widely as a journalist for El Mundo. His two best known books are the novels The Mad Toy (1926) and The Seven Madmen (1929). In these two books he attempted to find fictional form, using a mixture of the picaresque and a tone which was haunted and alienated, to capture his hero, a young man filled with a mixture of guilt and innocence, curiosity and knowingness, as he progresses from place to place.

It is possible that the first chapter of the book was written some years before the other ones, as Arlt sought to isolate his errant hero further, remove him from any group or circle, thus making his adventures all the more strange and alienating. The scene in the early pages of the book where Silvio and his companions ‘imagine that we lived in Paris, or foggy London town. We would dream in silence, a smile balanced on our condescending lips’ belongs to that world of literary young men feeling marooned in Buenos Aires, imagining the world of Europe as the real one, and locked into Argentina as though it were some kind of cage.

The only relief from life then was literature. In this world a book becomes a lethal weapon or a way of saving, or further staining, your soul which nothing else offered. Thus, even to this day, there is a something holy about a bookshop in Buenos Aires; the browsers and those who work in the shop give the impression that they are involved in some sacred ritual. A bookshop, then, is a natural place for Silvio to find and unfind himself in The Mad Toy. Baudelaire will be invoked as much as books about science and mathematics. ‘Sometimes at night I would think of the beauty with which poets made the world shake, and my heart would flood with pain, like a mouth filling with a scream.’

Arlt, the low priest of the modern, was fascinated by machinery as he was by literature and by magic and by sex. The scene with the man wearing women’s clothes would have been dynamite in the Buenos Aires of the 1920, as it remains deeply powerful to this day.

In this world only the hero is sane; much else is weird or monstrous. The day is filled with cruelty and ugliness; there are useless tasks to perform and many irritations. As in the world created by Borges, the night is more real, as is the world of dreams. The night, as invoked by words, can take on a stunning beauty, playing here a great game between shadow and substance, whose tone is quintessential to the book and endemic to its spirit:

Sometimes, at night, there are faces that appear, faces of women who wound you with the sword of sweetness. We move apart, and our soul remains shadowy and alone, as happens after a party.

Unusual apparitions… they disappear and we never hear of them again, but even so they accompany us at night, their eyes fixed on our own fixed eyes…. and we are wounded with the sword of sweetness, and imagine how the love of these women will be, these faces that enter into your own flesh. An anguished desert of the spirit, a transient luxury that is both harsh and demanding.

– Colm Tóibín, 2013

Introduction

There’s a point in the middle of the third chapter of The Mad Toy at which the reader is given for the first time the narrator’s full name: Silvio Drodman Astier. When I first read the novel, my initial reaction was to wonder if it was an anagram of the author’s real name. Of course it isn’t (no ‘B’, for starters, which is a problem if the name you’re looking for happens to be ‘Roberto’), but the impulse was excusable: one of the most immediately appealing things about Arlt’s novel is the sense it gives of being a record of events that we feel must actually have happened.

Where does this immediacy come from? In part it must derive from the way in which The Mad Toy, as is also the case with Arlt’s other novels, pins itself down firmly to a particular time and a particular place. If you take the time to look up on a map of Buenos Aires the street names Arlt mentions, you will see that most of the action of the novel takes place in a fairly small segment of a large city, the central districts of Caballito, Flores and Vélez Sársfield (where Arlt himself was born), with a couple of brief excursions to the docks and the Colegio Militar in El Palomar. For all his dreams of escape to London or Paris, dreams that are eventually only fulfilled to the extent that Silvio is offered a post in Comodoro, about 1,000 miles to the south of Buenos Aires, The Mad Toy is a local novel, alert to the detail of Silvio’s neighbourhood, the walls and alleyways, the cul-de-sacs, the milkbars, the green street lamps.

But the apparent realism of The Mad Toy serves to reveal the skill of the journalist, the professional observer of life. It is possible to be taken in by Arlt’s artistry to the extent of believing that Silvio must be an alter ego, but it is to do Arlt a disservice to think that Silvio is simply copied from life: the seemingly shapeless, picaresque nature of The Mad Toy is a grimy mask for an extremely carefully developed and formally patterned novel, in which the superficial story of Silvio’s adventures is also a detailed psychological portrait of Silvio himself. Of course, to a certain extent Silvio is inspired by Arlt: what first novel isn’t autobiographical to at least some degree? But it is more correct to say that Arlt managed to dissociate himself from the adolescent he had been, and created, with the benefit of hindsight, a fantastic version of his youth.

Arlt was born in Buenos Aires in 1900. He was the son of immigrants: his father was a Prussian, and so strict as to be perceived as unnecessarily cruel by his son; Arlt’s mother was from Trieste. Arlt had two sisters: one of them died in infancy; the other in 1936; both from tuberculosis. At the age of eight, Arlt was expelled from school, and his formal education ended. He worked at a number of jobs: he was employed for a while in a bookshop, but he was also a housepainter, a mechanic, a dock worker, a factory hand… Eventually the newspaper El Mundo employed him to write a column: his so-called Aguafuertes (‘Etchings’) of contemporary Buenos Aires formed a witty commentary on the city’s low-life. He also worked as secretary to the novelist Ricardo Güiraldes. His first novel, El juguete rabioso (The Mad Toy) was published in 1926, and was followed by Los siete locos (The Seven Madmen, 1929), Los lanzallamas (The Flamethrowers, 1931) and El amor brujo (Bewitching Love, 1932). In the 1930s Arlt began to write for the theatre, and by the end of his life was more or less exclusively a playwright. He died of a heart attack in 1942. Pieces of this biography crop up in The Mad Toy: Silvio’s sister is also called Lila and Silvio works in a bookshop for a while, but direct connections between Silvio and Roberto Arlt are few. However, there are a great number of subtextual connections, points at which Silvio can be seen as a projection of Arlt’s desires. Perhaps most significantly, as an act of revenge against his sadistic father, Arlt chooses to have Silvio’s father commit suicide: ‘my father killed himself when I was very young.’

Rather than being noticeable for its fidelity to real life, one of the most striking things about The Mad Toy is the occasional irruption of fantasy into the realist texture of Arlt’s prose. This is visible on certain obvious occasions, for example the disturbing dream sequence in chapter three: Silvio pursued across an asphalt plain by a gigantic bony arm. However, there is also an admixture of fantasy into supposedly realistic scenes. Following this nightmare, once Silvio wa

kes up, the prose deliberately treads the line between reality and fantasy. His encounter in the hotel room with the young man who tries to seduce him, although full of realistic details (the dirty clothing, the sordid environment of the hotel where the meeting takes place), is extremely oneiric: the description of the homosexual’s neck with its ‘triangle of black hair’ is an obvious sexual metonymy, and the shouts of the invisible guests fighting outside add to the dreamlike nature of the meeting. During the night, Silvio observes the homosexual and feels ‘a horror’ that gradually turns into ‘conformity’. One of the details Silvio notices about the homosexual is how a ‘lock of his carefully-arranged hair fell down’ when he turned his head. The next morning when Silvio wakes up, the bed where the homosexual had been is empty: more than that, ‘there was no trace that anyone had even slept in his bed’, and Silvio notices that his own hair is hanging down over his forehead.

It would be possible, and not too far-fetched, to read the whole sequence as a dream, a manifestation of Silvio’s buried desires (see also his homoerotic relationship with Enrique Irzubeta in chapter one, a chapter which climaxes with a naked Silvio hugging Irzubeta as both of them hide from the police). What is beyond a doubt is that Arlt uses, as few Latin American writers before him had done, the fantastic and the dreamlike as keys to a heightened realism, ways to give us a fully-rounded portrait of Silvio Astier. Silvio, with his love/hate relationship with Europe, his conviction that he is cut out for great things, his essential confusion and his frustration, is one of the first iterations of the modern Buenos Aires archetype, but in The Mad Toy the archetype is new, and Silvio is impressively individual.

Arlt is often celebrated as a writer who brought the language of the street into Argentinian letters, but this is not to suggest that he is an extremely colloquial writer: rather, he is a reporter who doesn’t soften the edges of the events he observes. Perhaps the closest comparison in English is with the early work of William S. Burroughs (Junkie, Queer), which presents low-life scenes in neutral prose, and reserves its linguistic innovation for the direct reporting of dialogue. Arlt’s dialogue is sparkily accurate, and stands slightly at odds with the occasionally clumsy soul-searching of Silvio’s conscience-stricken inner monologue. (The reader will have to decide if this clumsiness is authentically adolescent, or just… clumsy: I vote for the first option.)

The Seven Madmen

The Seven Madmen The Mad Toy

The Mad Toy